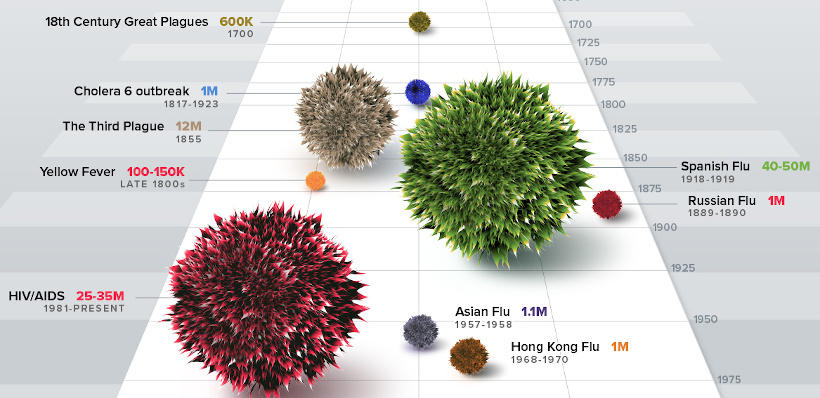

But with enough investigation, scientists have found nearly perfect matches of around 99 percent or better for some viruses-including the ones responsible for two previous coronavirus outbreaks.Ĭat-like tree-dwelling palm civets, considered a delicacy and sold in street markets, quickly became the focus during the 2002-04 outbreak of Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome (SARS) that emerged in China’s Guangdong Province, which resulted in more than 8,000 cases and nearly 800 deaths in 29 countries. The match may not be 100 percent, because viruses gather mutations or new genes over time and as they jump hosts. The laborious endeavor can take years until scientists have the evidence they need to point to a source.įor diseases originating from animals, that evidence is typically a genetic match between virus sequences obtained from an animal and those from some of the first confirmed patients. Tracing the origin of a virus requires extensive fieldwork, thorough forensics, and a fair bit of luck. Here’s what we know so far about the scientific investigation into the origin of the pandemic, and what still needs to be done to find clear answers. “But at some point, it crosses over from doing due diligence to wasting time and being crazy. “There is a progenitor virus out there somewhere, and we should look for it,” says David Morens, senior scientific adviser on epidemiology to Anthony Fauci, director of the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases. Other experts caution that political motivations could drive people to hasty conclusions. That WHO report also deemed a laboratory leak from the Wuhan Institute of Virology, known for its work with coronaviruses, as “extremely unlikely.” But the conclusion sparked backlash from scientists and governments around the world, who argued that it’s still too early to rule out a lab leak based on the evidence in hand. Similarly, the 2012 MERS-CoV epidemic is suspected to have originated in bats and was later transmitted to dromedary camels, which infected humans. This was the case with the 2002 SARS-CoV outbreak- the first pandemic of the 21st century the virus most likely spilled over from cave-dwelling horseshoe bats in China to palm civets sold in live animal markets, where it reached humans. In a report that summarized their findings, the WHO suggested that it was “likely to very likely” that the virus first spread from infected bats to humans via an intermediate host animal.

“To go back and confidently identify the source is a difficult task.”Įarlier this year, an international World Health Organization team visited the city of Wuhan, China, to assess the evidence China had provided about the origin of SARS-CoV-2. “Science takes time,” says Arinjay Banerjee, a virologist at the University of Saskatchewan in Canada. But similar inquires during past epidemics have taken months to years to yield answers, and in several cases, the mystery remains unresolved. That’s why scientists support a thorough, evidence-based investigation for the origins of COVID-19. And if the virus is instead found to have leaked from a lab, that finding would no doubt spur scientists and policy-makers to find safer ways to study these pathogens. Knowing where the pandemic virus arose could also lead to changes in human behavior, such as reducing demand for bushmeat and wildlife-derived products that drive the illegal wildlife trade. The results may also lead to broader policy decisions to curb deforestation and habitat fragmentation, and to block human settlements in known viral hot zones. Measures could involve regular surveillance of animals and humans living where the virus is endemic to reduce the likelihood of future spillover-when a virus is transmitted to a human, directly or via a host animal, triggering an outbreak. If the source of the virus is found to be bats or another animal, as many experts suspect, preventative measures might include curtailing contact between that animal and those living or working in close proximity. Understanding where, when, and how this pandemic started is important information for public health officials seeking to control its spread and even prevent future outbreaks. A brief, one-page unclassified summary released on August 27 revealed the only point on which the intelligence community agreed: that the virus was “not developed as a biological weapon.” intelligence community came up empty-handed on the origin of the SARS-CoV-2 virus.

Most experts were not surprised in late August when a 90-day investigation by the U.S. But the most polarizing question and central mystery remains: We still don’t know where the virus that started it all actually came from. After 20 months, 219 million cases, and more than four million deaths, we’ve learned a lot about the COVID-19 pandemic.

0 kommentar(er)

0 kommentar(er)